Over the High Street entrance to my college in Oxford stands a statue of Cecil John Rhodes, archimperialist of the nineteenth century, a man who wanted to make it possible to travel from the Cape to Cairo without ever having to leave British territory. Rhodes was, without doubt, the source of much evil in the history of Southern Africa. The legislation that he introduced as prime minister of the Cape Colony pushed black people off their land and raised the property qualification that they needed to satisfy in order to vote. These were laws which helped lay the foundations of apartheid.

The statue of Cecil John Rhodes

being covered by protestors.

The statue is now covered over

with wooden boards.

|

Another

statue of Rhodes, not in Oxford, but on the southern tip of the African

continent, has become the focal point of a student protest movement whose name

and rallying cry is ‘Rhodes Must Fall’. Last month, this statue,

sitting in the middle of the campus of the University of Cape Town (UCT), had a

bucket of poo thrown over it. Since then, students have been

calling loudly for the removal of Rhodes’ image as part of the ‘decolonisation'

of the university more generally.

Critics of 'Rhodes Must Fall' claim that the campaigners are

attempting to ‘cleanse

history of its veracity’. However, it is

simply not true that pulling down the statue of Rhodes is the same as

pretending that the acropolis or the forum weren’t 'built by the sweat of

slaves and the grinding oppression of the slaveowners'. I've read no one suggesting

that Rhodes' name should be removed from the history books, only that it is

time to stop publicly glorifying those men who helped to create the sorts of

injustices and inequalities that still characterise so much of South African

society.

That Rhodes still sits at

the heart of the UCT campus is emblematic of the way that the economic, academic and social

privileges of white South Africa persist even in 2015. Just like other white

South Africans, my life and career in the academy has been made easier by these

privileges. In a country where nearly 80% of the population is black, only 3% of academic staff at UCT are, and there

is only one black woman who holds the title of full professor, while 111 white men can lay claim to this honour.

Statues,

like all symbols, have power. This is something that the Romans knew well. When

they deposed ‘bad emperors’ or political enemies they also deposed their

statues. Statues could be mutilated or torn down, portraits erased, names

scratched off the coins and inscriptions that celebrated the fallen tyrant’s

achievements. This is often referred to as damnatio memoriae, literally ‘damnation of memory’.

Memoria meant more for the Romans than the word ‘memory’ really gets across. It was the key to a kind of afterlife, a way that everyone, from freed slaves to emperors, could ensure that they lived on, even if only in the memories of the people that passed by their tombs, saw their statues, or read inscriptions celebrating their deeds. Memory sanctions shut down routes to this sort of immortality by erasing or defacing a person’s name or image. For emperors, who could normally expect to join the gods after they died, this was a clear sign that there was no room for them in heaven.

|

Lucius Aelius Sejanus had memory sanctions

imposed on him after a conspiracy to overthrow

the emperor Tiberius failed. This coin was later

defaced to remove his name.

|

Sometimes

the aim of this was oblivion, sometimes a visible show of disrespect. Of course,

this can make it difficult for historians to study certain aspects of the past. However, damnatio memoriae shouldn’t

be thought of as a veil that hides historical truth. Removing this veil

would not reveal the past to us in perfect clarity.

Far from obscuring our view of history, how the Romans treated images

of 'bad emperors' is the very stuff of

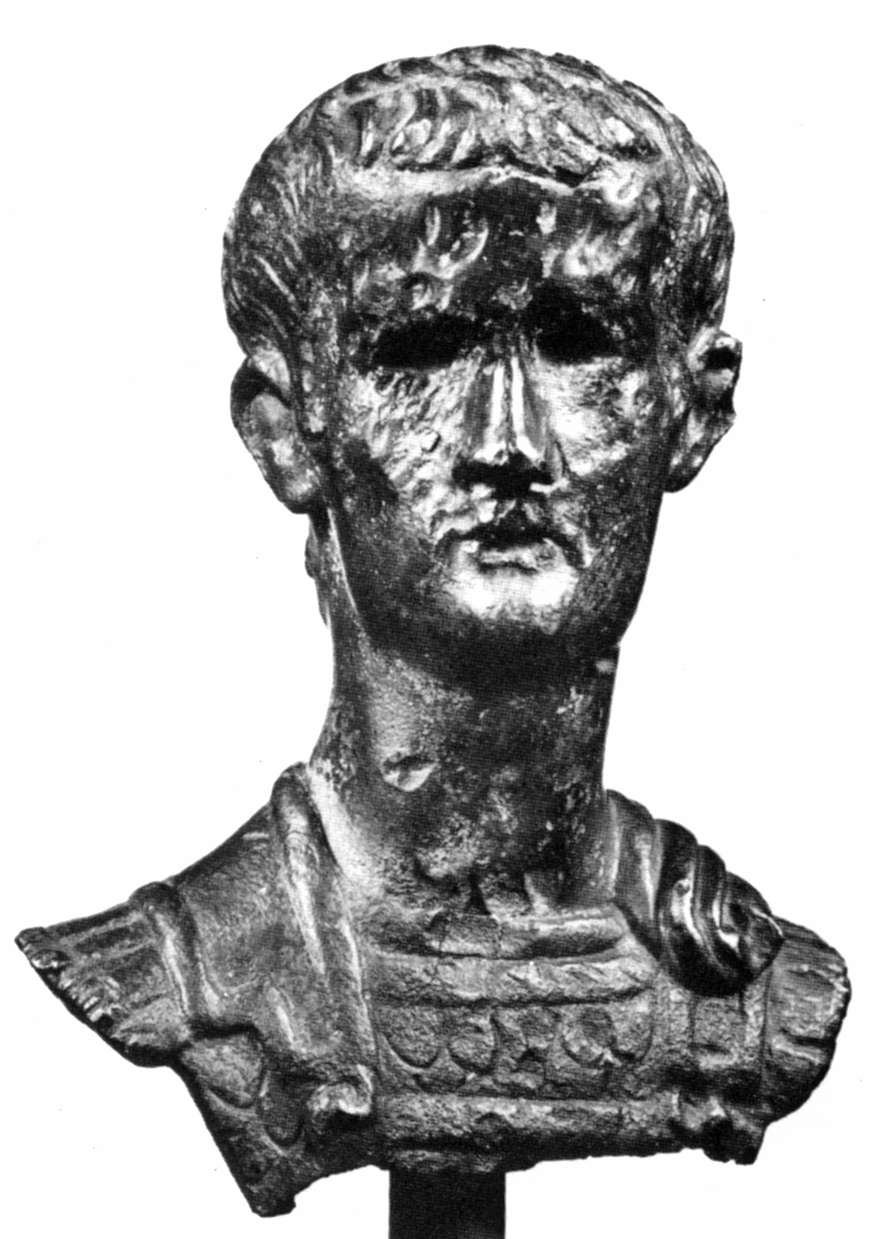

history. Coins like the one above or statues like the one below tell us much more about the past than they would if they had been left unaltered. To assume that their defacement in some way detracts from their historical value is to forget that Roman emperors carefully managed the way they appeared in public art. Even before these images were altered they were not uncomplicated records that simply told THE truth.

|

| Bust of the emperor Caligula. The statue's eyes have been gouged out and the face has been attacked. |

The same is true in Rhodes' case. Sitting where it does now, his statue tells only one history. Keeping

it there does not give us a clear vision of South

Africa's past. But, throwing poo at it or removing it does tell us something about how the present understands and relates to this past. The Romans knew that a statue could keep a

man and his deeds alive even after he was long dead. It could set him amongst

the gods or send him to Hades. The question that South Africans have to ask is

which of these two fates they wish for Rhodes and his legacy.

No comments:

Post a Comment